Missing megaflood: How did the Mediterranean transform from a salt-filled bowl to a deep sea if it wasn’t a cataclysmic deluge?

On October 6, 1970, the deep-sea drilling vessel Glomar Challenger returned to port in Lisbon, Portugal, bearing a cargo that would revise history. During its 54-day voyage, the Challenger had punched 28 holes into the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea. The recovered cores pointed toward a startling conclusion: About 6 million years ago, the sea had turned into a desert: a vast, barren, salt-filled bowl more than two kilometers [1.2 miles] deep. Half a million years after that, the Atlantic Ocean had burst through what is now the Strait of Gibraltar and unleashed the largest flood in history.

Kenneth Hsü, an oceanographer who was one of the two lead scientists on the Challenger expedition, imagined the scene vividly in the December 1972 issue of Scientific American:

“Cascading at a rate of 10,000 cubic miles per year, the Gibraltar Falls would have been 100 times bigger than Victoria Falls and 1,000 times more so than Niagara.… What a spectacle it must have been for the African ape-men, if any were lured by the thunderous roar.”

The catastrophe story was a hit: David Attenborough filmed a documentary about it, and Gibraltar even issued a 5-pence stamp portraying the “3,000-metre waterfall.” The two hypotheses — first, that the Mediterranean Sea became landlocked during a half-million-year period known as the Messinian salinity crisis, and second, that it was restored by a cataclysmic deluge through the Strait of Gibraltar, dubbed the Zanclean flood — have been conventional wisdom among geologists for more than 50 years.

However, fresh doubts have arisen recently about every part of this story, from the mega-desert to the mega-Niagara. Many geologists have argued for a much briefer desiccation followed by a far more gradual refilling of the Mediterranean. Some think that the Mediterranean never completely disconnected from the Atlantic at all. “The idea of a megaflood, and the data that supports it, are mostly flawed,” says Guillermo Booth Rea of the University of Granada in Spain.

The most startling recent twist is that the floodway, if there was one, may not have been anywhere near the present-day Strait of Gibraltar, which separates southern Spain from Morocco. For 50 years, new research suggests, we have been looking for signs of a megaflood in the wrong place.

A geological conundrum

In the present-day Mediterranean, about three times more water is lost every year to evaporation than is recaptured from rainfall and rivers. The Atlantic makes up for the difference, supplying a steady west-to-east current of seawater through the Strait of Gibraltar. As the sea’s water evaporates, the remaining water becomes saltier and denser and sinks to the bottom. The dense water then flows back out of the strait, east to west, underneath the less dense inbound water. This outflow prevents salt from accumulating in the Mediterranean.

But what would happen if the strait were constricted, or shut off entirely? Given the hugely negative budget of fresh water, “sea level” in the Mediterranean Sea would drop rapidly, by as much as a kilometer in 2,000 years. Such a scenario would have seemed like science fiction until the Glomar Challenger’s 1970 expedition.

At the first drill site, the Challenger’s drill bit jammed on a very hard layer 200 meters below the bottom of the sea. The next day, Hsü and his co-lead scientist, William Ryan of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, found out why. “It brought up buckets full of gravel,” Ryan says.

Seafloors don’t often contain beds of gravel, and when they do, it is usually continental rocks washed down from the adjacent land. But this gravel had marine fossils and rock, mixed with crystals of gypsum. Geologists call gypsum an “evaporite,” because in the present-day world it forms in evaporating shallow bodies of water — as in the Dead Sea, for example. The implication was startling. “When Ken held up the gypsum crystals, he turned to me and asked, ‘Do you think the Mediterranean dried out?'” Ryan remembers.

The same story was repeated at every stop. Ryan and Hsü found other evaporites like halite (sodium chloride, aka table salt). Oxygen isotopes in seashells embedded in the gravel suggested that these unlucky animals had lived in a brine from which 90 percent of the original water had evaporated. Hsü and Ryan also gathered evidence that the colliding of the African and Eurasian tectonic plates had lifted up the land on both ends of the Mediterranean Sea, closing its former connection with the Indian Ocean and narrowing the connection with the Atlantic Ocean.

The clinching piece of evidence came to light after the Challenger mission had ended. Other geologists discovered what appear to be buried ancient beds of several rivers that flow into the Mediterranean, particularly the Nile and the Rhône. It looked as if those rivers once emptied into the Mediterranean at least a kilometer below their present outlets — something that would be possible only if the sea level of the Mediterranean had been a kilometer [0.6 miles] below the global sea level at some point in the past.

In 1973, a meeting in Utrecht, Netherlands, established the desiccation model as the consensus theory. But a considerable amount of dissent has emerged in the last 20 years. “In the 1970s, the desiccation people won the debate,” says Wout Krijgsman of Utrecht University, “but there are several aspects it cannot really explain.”

Paradoxes galore

In part, the dissent reflects an improved understanding of what was occurring on Earth and in the area 6 million years ago. Since 1973, the story told by rocks, core samples and seismic soundings — and, increasingly, by computer simulations — has become more detailed and more dynamic, with changing shorelines, land bridges and volcanoes, and repeated episodes of climate change.

Also, there were fundamental problems with the desiccation hypothesis to begin with. Take the evaporites, for example: They do not have to form via evaporation, says sedimentologist and stratigrapher Vinicio Manzi of the University of Parma in Italy. They can also form by precipitation from a sufficiently concentrated brine. This can happen underwater, so there is no need to posit that the Mediterranean went bone dry.

And the buried riverbeds? Those, too, Manzi and his colleagues can explain: The sinking of briny water can produce downhill currents (“dense shelf water cascading,” in geology lingo) sufficiently strong to scour out a canyon.

The idea of a single evaporation event also faces a mathematical problem: The existing salt deposit is too big to be explained by a single evaporation event. It represents about 5 percent of the salt in the world’s oceans (and may have originally been 7 to 10 percent). To collect that much salt, the Mediterranean would have had to empty and refill about 10 times.

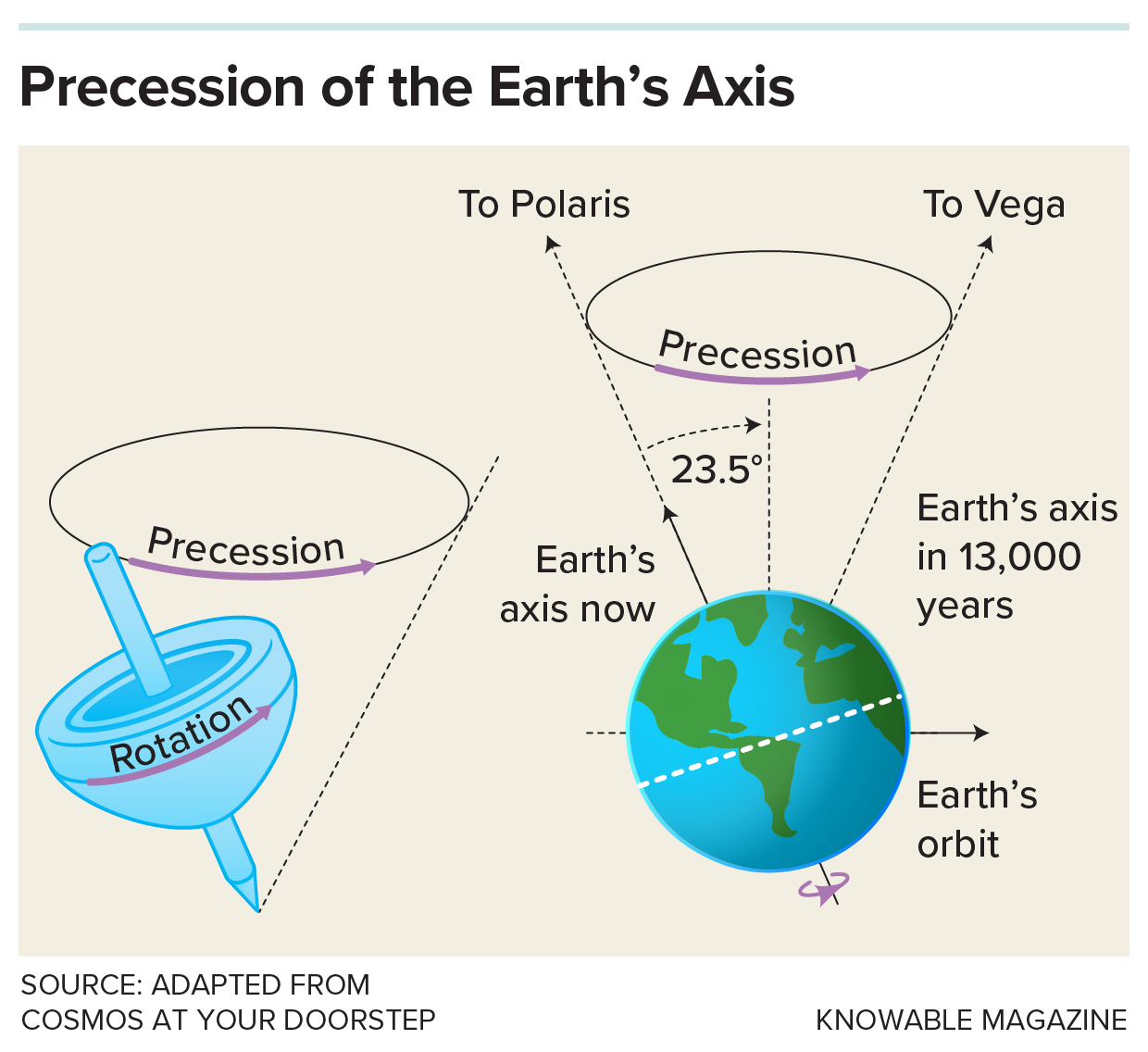

In fact, evidence from salt deposits in Sicily suggests something like that actually happened. There, gypsum beds alternate with shale beds that are rich in organic material and could have formed in periods when the gateway between the Atlantic and Mediterranean was open. There are 16 beds in all, with ages spaced about 23,000 years apart.

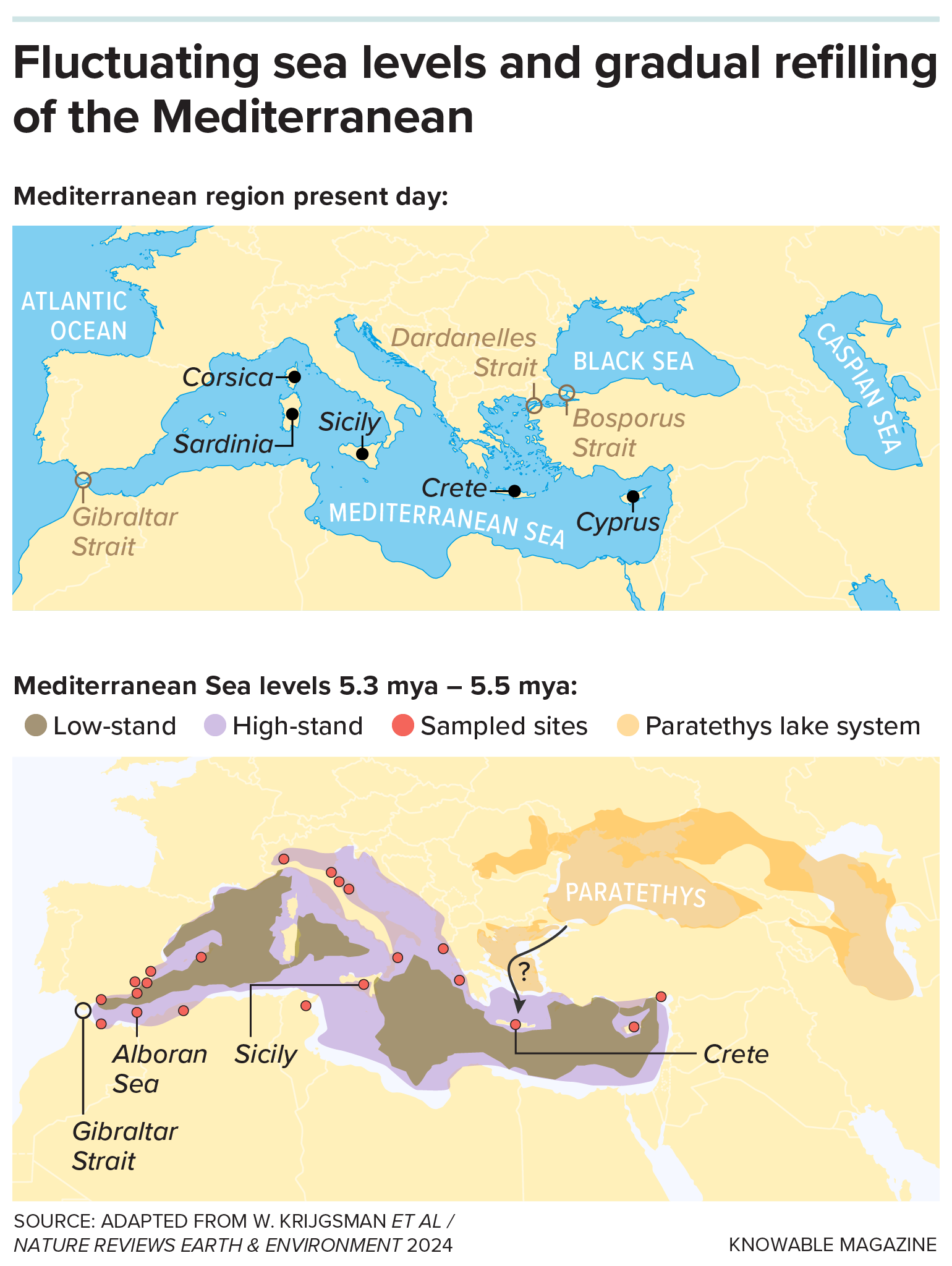

This periodicity is well known to geologists: It’s the time it takes for Earth’s axis (like a wobbly top) to trace one complete circle. And it correlates with changes in climate and ancient sea levels the world over. With the presumptive Gibraltar gateway being so shallow during this period, sea level fluctuations due to this “precessional cycle” could have repeatedly opened and closed the connection between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic.

That period of gypsum formation is now called Stage 1 of the salinity crisis. Stage 2 was a relatively brief 50,000-year period when (in the majority opinion) the gateway slammed entirely shut, the sea level in the Mediterranean plummeted, and huge deposits of halite (sodium chloride) precipitated out from the seawater. However, Manzi’s group strongly dissents, arguing that the Gibraltar gateway remained open, but shallowed to such an extent that the water flowed through it in one direction only — in but not out — resulting in a runaway buildup of salt.

Even for adherents of the majority view, Stage 2 is not as simple as it seems. Data from chlorine isotopes suggest that the drawdown was not uniform. At its lowest point, in the western Mediterranean, sea level was 800 meters below its present level, while east of present-day Sicily it was at least twice as deep as that. If so, the east and west portions must have been separated by a land bridge. Indeed, there is evidence of African animals crossing over to Europe during this time.

The last 200,000 years of the salinity crisis, called Stage 3, have been the most puzzling of all. The halite stopped precipitating and there is evidence for a variety of sea levels in the Mediterranean during this time. Widespread fossils of a shrimp-like animal called an ostracod suggest that the waters became much less salty, so that the Mediterranean was a sea-sized lake (and indeed, this stage is sometimes called the Lago-Mare stage). But if the gateway to the Atlantic was still closed, then where did the fresher water come from?

A 2025 paper by Daniel García-Castellanos of the Spanish National Research Council helps solve the puzzle. Using a computer to model erosion, he argues that the Mediterranean was gradually refilling during Stage 3. The ostracods provide a clue to the source. They originated from the area of the present-day Black and Caspian Seas, which back then were connected to each other, but not to the Mediterranean.

With the shores of the Mediterranean being so newly exposed and so steep, its edges would have rapidly eroded toward today’s Black Sea, which at that time was a much larger freshwater lake called the Paratethys. The first connection between them could have been established at this time. If so, the Mediterranean began to receive waters from rivers like the Volga, the Don and the Danube, which had previously been unavailable. The ostracods got a new home, and the Mediterranean got a vast new supply of water, which according to the computer simulation raised its surface to within 300 meters of its current level.

According Krijgsman, this interpretation conveniently reconciles the conflicting evidence. “In the fight between a desiccated and full Mediterranean,” says Krijgsman, García-Castellanos’ paper does the job “if you want to sit in the middle and give everyone credit for their observations.”

Missing: One megaflood

The literature on the Messinian salinity crisis is voluminous, and yet one thing is curiously absent. There is surprisingly little direct evidence of the megaflood that supposedly ended the crisis. Hsü’s original Scientific American article devotes only half a page to it and adduces little in the way of evidence. Fifty years later, Ryan wrote a 100-page retrospective; only three pages are about the megaflood. Shouldn’t this extraordinary flood have left very clear scars?

The current evidence is ambiguous at best. Geologists have found submerged flood-like deposits off Malta — but that’s a long way from Gibraltar, the putative source of the flood. Also, if the Atlantic drained into a nearly empty Mediterranean basin, then sea levels around the world should have dropped by about nine meters — an anti-flood to pay for the Mediterranean flood. There is no sign that this happened, says García-Castellanos.

A recent deep-sea drilling expedition to the Strait of Gibraltar turned up more questions than answers. In December 2023, the JOIDES Resolution — heir to the Glomar Challenger — revisited the Alboran Sea immediately to the east of the Strait of Gibraltar. If the strait is the door to the Mediterranean, then the Alboran Sea is the vestibule. Any megaflood that passed through the Strait of Gibraltar would have passed also through the Alboran basin. But Rachel Flecker of the University of Bristol, England, co-leader of the expedition, says they found no traces of the flood in the cores they collected.

While still on board the ship, she wrote that the cores were “exquisitely laminated in a variety of colors. This incredibly fine lamination requires very quiet, low energy conditions.” Exactly the opposite of a megaflood. Final results have not been published yet, but Flecker reports also that they found no salt layer and no evidence that the salinity crisis had ever touched the Alboran Sea.

“The connection between the Atlantic and Mediterranean before and during the Messinian salinity crisis wasn’t through Gibraltar,” she concludes.

How can this be? “A feature that you must take into account, and nearly nobody does, is that the present physiography of the Mediterranean is very different from the Messinian one,” says Booth Rea. “Large basins have opened since, like the Tyrrhenian; other regions have emerged, like Sicily.” One possibility, he suggested, is that the gateway was somewhere to the east, through a volcanic arc of islands that once connected Africa to the Balearic Islands. Other possibilities include channels through Spain or Morocco, which are above sea level now but were underwater as recently as 7 million years ago.

Regardless of how it happened, this modern view of the story holds lessons: It emphasizes the power not of dramatic events but of small changes. “Salt giants” — that is, massive salt deposits like the one underneath the Mediterranean — have formed at other times in Earth’s history, when basins were trapped between two tectonic plates. Their effects on climate and biodiversity have likely been huge: In this event, 89 percent of exclusively Mediterranean marine species died out.

And a slight shallowing of the Strait of Gibraltar (or whatever the true gateway was) might be all that was needed to trigger these vast changes. “In some sense, this is more terrifying,” says Manzi, because it shows that “you can reach extreme conditions without extreme events.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.