Deep-pocketed investors are snapping up Canadian fertility clinics at a rapid pace and making a fortune. Public health care might be a sacred cow in Canada, but the money-making potential of the private IVF industry is ‘staggering’

Article content

Nancy Abdalla was 36 years old and tired of putting her energy into relationships that flamed, fizzled and ultimately got her nowhere closer to what she wanted: a baby. Her girlfriends were having kids and she could not imagine a future without having one of her own, even if that meant going it alone instead of waiting around for Mr. Right.

But waiting was the problem. Back in her career-focused 20s, nobody bothered to tell her that female fertility dives off the cliff precisely at the age when the marketing consultant finally decided to try to have a child. Her doctor sent her to a fertility clinic in Toronto that ran a battery of tests that concluded her reserve of eggs was in short supply and that she had a “geriatric” fertility profile.

Article content

Article content

Advertisement 2

Article content

No one shows up at a fertility clinic because they want to be there

Nancy Abdalla, mother

Thus began a multi-year journey with good chunks of it spent in the clinic’s waiting room in the wee morning hours alongside other women, working on laptops and anxious to get their bloodwork done so they could get to their jobs.

Article content

“No one shows up at a fertility clinic because they want to be there,” she said.

Abdalla said the clinic had the feel of an “airport” departure lounge, and she saw herself as a cog in a great wheel of aspirational motherhood. Had her doctor told her “to stand on one leg and dance like a chicken” to better her odds of having a child, she would have done it.

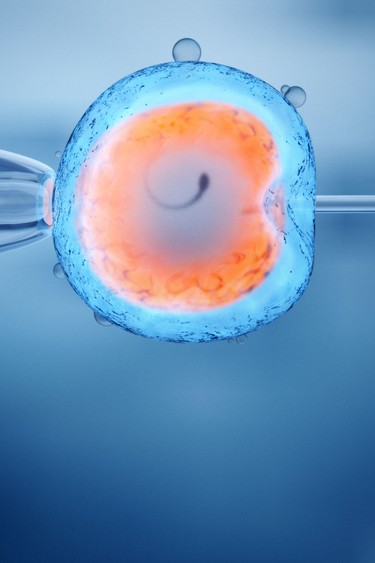

In the end, no dancing was required. There were two unsuccessful egg retrievals, three failed intrauterine inseminations, multiple in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles, three failed embryo transfers and, at long last and after about $100,000, a child, who today is four years old, as well as the husband she met mid-journey who declared himself in for the long haul by donating sperm to a cause that was ultimately successful with the help of a donor’s egg.

Article content

Abdalla is not the only happy one. Deep-pocketed investors have been buying up Canadian fertility clinics at a prodigious rate and are happily making money. Publicly funded health care is a sacred cow in Canada, but having a child can be a private, for-profit undertaking.

Article content

The Lancet, an independent, international general medical journal, pegged the global fertility market’s value at US$34.7 billion in 2023 and projected that to nearly double within a decade, boiling the industry’s money-making potential down to a single word: “staggering.”

Doctor-owned clinics used to be the norm, but of the approximately 46 Canadian clinics in operation, 22 are now owned by private equity, 21 are physician-owned and three are attached to public hospitals, according to the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society (CFAS), a national non-profit that includes a mixed bag of reproductive specialists, doctors, administrators and more.

“When you look at the impact of private equity, the net effect is those partners want to make a lot of money,” Sarah Kaplan, professor emerita of strategic management at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, said. “They are not just trying to live in a nice house in the suburbs comfortably; they want private jet money and where does that jet money come from? People are stretching their savings to try to get pregnant because they really want to have a family.”

One in six couples experience infertility

Fertility patient costs, as Abdalla found out, can be extreme, but even the average customer who enters a top-performing Canadian fertility clinic will require two or three IVF cycles to leave with a baby at $15,000 a pop — give or take.

Article content

Patients are highly motivated and emotionally vulnerable, and there is always someone next in line, given that one in six Canadian couples experience infertility and close to 30,000 women in any given year are receiving fertility treatment.

Governments in British Columbia, Quebec and Ontario all offer at least one wholly or partially funded IVF cycle along with a mishmash of tax credits, further expanding the pool of potential customers and upping the inclination among investors to get a piece of the action.

The Fertility Partners Inc. is a clinic consolidator founded in 2019 by Andrew Meikle. A dentist by trade, he helped drive dental practice consolidation in Canada through a previous business, Dentalcorp. His relatively new baby was backed by an initial $90-million investment by Toronto-based Peloton Capital Management Inc. Australia’s HEAL Partners Management Pty Ltd. also invested an undisclosed sum.

Peloton’s chair is billionaire banker Stephen Smith of First National Financial LP, who presumably recognizes a good opportunity when he sees one, as does David Thomson, often described as the richest person in Canada. He is active in the fertility space through Osmington Inc., a Thomson-owned private investment firm that put up $20 million in seed money to help launch a numbered company known as Pollin Fertility, a Toronto-based startup with aspirations of growing nationally.

Article content

Elsewhere, private-equity heavyweight KKR & Co. Inc. in January 2023 paid close to US$4 billion to acquire IVIRMA Global SL, a Spanish company that has around 200 fertility clinics worldwide, including several clinics in Ontario operating under the Trio Fertility banner, one of which is the longest-running IVF lab in Canada.

Convincing a private-equity firm to discuss their Canadian investments is apparently harder than making a baby. Interview requests were declined or ignored altogether. But one private-equity professional familiar with the North American fertility clinic landscape who agreed to talk on the condition they remain anonymous said there are only so many opportunities in the Canadian health-care space that feature private user-pay models, including dental clinics, physiotherapists, veterinarians and fertility specialists.

They said people paying out of pocket for a service eliminates any “stroke-of-the-pen risk” where a change in government policy can shut off the money taps. In other words, the money is there for the taking, especially if a company can create efficiencies.

The redeeming and virtuous point of private equity doing this is raising the quality of care across a network

Private-equity insider

Fertility clinic A may have different standards of care than clinic B, and both may have different models than clinic C, as well as different accounting and human resources procedures, all of which smack of inefficiency. The insider said by “rolling up the clinics,” private equity can streamline practices and platforms and negotiate at scale with health-care vendors.

Article content

Consolidation also allows for knowledge sharing across the network. More efficient clinics, in theory, can accommodate more patients; more patients means more profit. Prices per patient typically increase when private equity gets involved, as can clinic success rates. The industry in Canada is also loosely regulated, so there is not a ton of oversight.

“The redeeming and virtuous point of private equity doing this is raising the quality of care across a network,” the insider said.

Of course, private equity is in it for the money and will eventually look to make a lucrative exit from the business, while someone who desperately wants to have a child is reduced to a profit point for those flitting about in private jets.

But private equity’s presence in fertility clinics is nothing nefarious, according to Arthur Leader, a 79-year-old professor emeritus of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive medicine at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Medicine.

He and another doctor in the early 1980s established the first IVF research program in Calgary and the science of making babies has come a long way since then. In the old days, dealing with blocked fallopian tubes was the extent of the available expertise and, at best, IVF success rates topped out at about 10 per cent.

Article content

Article content

A well-run commercial clinic today should have a 50 per cent success rate, Leader said, but the “consumer” has no way of differentiating between clinics that are batting .500 and ones that are falling short.

A few years ago, he filed a freedom of information request, paid a fee and waited 12 months to get his hands on fertility clinic data from Ontario’s Ministry of Health. Individual clinics are not identified by name in the data, but were instead assigned a letter.

Clinic J no doubt appreciated the anonymity since it had a live birth rate of 7.9 per cent, meaning less than one in 10 women went home with a baby. Clinic K, meanwhile, had a 45 per cent success rate, a percentage that increased to 61.2 among women 35 and under. Clinic J’s numbers similarly improved with a younger patient cohort, but still failed to crack 10 per cent.

“I have nothing against there being corporate involvement in the fertility field,” Leader said. “But from the consumer standpoint, I don’t know if you want to call it truth or whatever word you want to use, but there is no transparency.”

‘It is a gimmick’

Equally problematic and pricey are the add-on treatments and tests, such as pre-implantation genetic testing, a.k.a. PGT-A, which screens embryos for extra or missing chromosomes. The test can cost anywhere from $2,500 to $5,000 or even more.

Article content

In select cases, particularly for women over 35 who have experienced multiple miscarriages, the test may be worth considering, according to Mount Sinai, a hospital in Toronto. But having the test done does not improve a woman’s odds of having a baby. CFAS recommends the test “not be routinely done,” but the numbers suggest it is becoming standard practice. In 2019, 21 per cent of all fresh embryo transfers underwent screening; five years later, 37.8 per cent did.

“It is a gimmick,” Leader said. “Studies have shown over and over and over again that the chance of having a healthy live-born child is not increased by doing this test; these are unnecessary expenditures for the consumer.”

But Kerry Bowman, a bioethicist at the University of Toronto who has consulted on hundreds of fertility cases, said consumers can often be their own worst enemy in terms of controlling costs.

People who show up at a fertility clinic “really, really, really want a baby,” he said, and even when they are told their chances of a successful pregnancy are, say, less than five per cent and potentially less than two per cent, a typical response is still “Let’s go for it.” Going for it may include undergoing multiple IVF rounds and willingly spending an unknown amount of money in the face of long odds.

Article content

“The industry is market driven, but you tend to get consent for treatment,” he said. “There is no question people are vulnerable, but from a point of view of consent, ethically, can you say to a couple, ‘You are so emotionally overwrought and you’re so wrapped up in this that I worry you’re not capable of making a clear-eyed decision?’ You can’t.”

Melody Adhami knows firsthand what the emotional rollercoaster of infertility can be like. She is a co-founder of Pollin Fertility and a former tech entrepreneur and co-founder of Plastic Mobile with her husband, Sep Seyedi. The mobile app maker boasted several big-name Canadian corporate clients and was eventually bought for an undisclosed sum by a French company, at which point she could have retired to a life of looking after “her tomato plants” at a vacation property north of Toronto.

At age 39, with three kids and no history of ever having difficulty getting pregnant, she and Seyedi decided it was “now or never” to try for number four. Lo and behold, 39 is not the new 29, and the couple found themselves at a fertility clinic.

“All of it felt very impersonal and you just have to go through the process,” she said. “Right from the get-go as an entrepreneur, my thinking was, ‘This can be done so much better.’”

Article content

Today, Adhami has a six-month-old at home and an investor group that includes a billionaire. Her business case when pitching a new clinic was that one in six Canadians experience infertility, women are having children later in life, male fertility is on the decline and the medical field seems underserved from a tech perspective, so it is ripe for disruption. The ace in the hole, she said, is that everybody knows someone who has been through IVF.

Patients at Pollin can get their results, book appointments and make payments through an app, and Adhami said the focus from the outset has been on open communications that put the patient first, while the long-term plan is to build out a system that can help mine the clinical data to produce better outcomes.

“The goal has never been volume,” she said. “The No. 1 goal is success rates.”

Being an entrepreneur, she understands there is pressure to make a buck, but she said profitability has not appeared on any meeting agenda in her quarterly sit-downs with Pollin’s board. Sure, professional dealmakers eventually want growth, but they also want smart growth. Meanwhile, the message being pushed by her investors has been to focus on quality of care and reputation building.

Article content

“The question is never, ‘Will you make more money?’” she said.

Adhami, a self-admitted data nerd because data tells a story, said the story in Canada boils down to the consumer flying blind, whereas that’s not the case in the United States, where fertility clinics are bound by law — and have been since 1992 — to report their success rates. The information is freely available to American consumers, so patients can comparison shop and they have the tools required to do so.

Article content

“I am 100 per cent a proponent of opening up and being transparent with people’s success rates because that’s what will lead you to be better,” she said. “If it was very clear who was what and where they ranked, and if there was an expectation on the clinics, then more people would be accountable to their numbers.”

Data from U.S. fertility clinics weaves a compelling business case around consolidation, Ambar La Forgia, an assistant professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, said.

U.S. clinics used to be single-doctor-owned enterprises until doctors started buying one another out. At a certain point, private equity would enter the picture and provide the capital necessary for further expansion. What La Forgia discovered, and her data sets end at 2018, is that a clinic would increase its number of IVF cycles by 27.2 per cent after being acquired by a chain and boost its success rate by 13.6 per cent. In other words, bigger proved to be better for both the patient and for the bottom line.

Article content

“What I found was private equity was really, really good at helping to increase the number of IVF cycles,” she said.

Private equity, of course, is not the only game in town. In somewhat of a throwback move, doctors Crystal Chan, Meivys Garcia and Marta Weis in 2021 purchased the Markham Fertility Centre in Ontario from its founder, Michael Virro.

“Because we are the owners, we have the freedom to put patients in front of profits,” Chan said.

She is not, however, bashing private equity. Investors call her up all the time to ask whether she and her partners want to sell. Twenty years down the road when she is closer to retirement age, perhaps the answer will be yes.

Chan said she can see the attraction of private equity, given its ability to drive economies of scale, improve a lab’s purchasing power for equipment and disposables, and, by extension and in theory, drive down the price of IVF treatment.

She and her colleagues have spent a lot of time thinking about the impact of private equity on their profession and sifting through pricing models across clinics. By her calculation, private-equity-owned clinics have higher fees than sole proprietorships, independents or university-owned clinics.

Article content

“Private equity doesn’t seem to be driving the prices down and we also don’t have any evidence that PE-owned clinics improve safety or efficacy of IVF,” she said.

But it is not a simple case of good versus bad, she said, since “you can have really crappy independent clinics and you can have really great PE clinics.”

A big perk of being an independent, Chan said, is that she and her partners are not beholden to investors, so the only people they have to answer to are “patients, staff and themselves.”

Private equity may even act as an unequivocal force for good in certain arenas, Kaplan said. For example, say a certain technology is now out of date and a company requires reinvention and fast. The private-equity “mindset” of extracting profit from the old ways as an enterprise pivots to the new ways can result in a transformational win for everybody. But applying that same mindset to extracting profit from people trying to get pregnant who have run out of other options is a worrisome can of worms.

“I feel like the incentives of private equity are not aligned with the needs of families,” she said.

But endings, especially happy ones, can minimize the messy details required to get there. Don’t bother asking Abdalla about money regrets; she is too busy caring for her son, Hendrix, who “melts” his mother’s heart.

“I can’t even think of all the money I spent because none of that outweighs having my son,” she said. “He is the joy of our lives.”

• Email: joconnor@postmedia.com

Article content